The Tschuggen is the highest point on the ridge which separates Grindelwald and the Lauterbrunnen Valley, and which includes the much better known Lauberhorn and Männlichen. Though there is no track, access to the summit is not dif ficult. It has just about the best possible view of the Eiger, Mönch and Jungfrau summits.

The weather at the start of September was once again mixed and at times cool, with

no more than brief sunny intervals. I remembered the worrying suggestion I had read somewhere

that weather like this might become the norm in Switzerland if climate change was moving the

jetstream further south than it used to be at this time of year. There had been

some snow down to levels below 3000 metres, so I needed to pick a peak somewhere

in the mid 2000s. There was one good candidate nearby... the Tschuggen. It was

something of an orphan in the walking Eldorado of Lauterbrunnen and Kleine

Scheidegg, where most prominent tops have several means of access, in that

there is no marked or mapped walking track to the summit at all. And what made it

an even better candidate was that I had never been there before.

The weather at the start of September was once again mixed and at times cool, with

no more than brief sunny intervals. I remembered the worrying suggestion I had read somewhere

that weather like this might become the norm in Switzerland if climate change was moving the

jetstream further south than it used to be at this time of year. There had been

some snow down to levels below 3000 metres, so I needed to pick a peak somewhere

in the mid 2000s. There was one good candidate nearby... the Tschuggen. It was

something of an orphan in the walking Eldorado of Lauterbrunnen and Kleine

Scheidegg, where most prominent tops have several means of access, in that

there is no marked or mapped walking track to the summit at all. And what made it

an even better candidate was that I had never been there before.

Accordingly, I drove to Lauterbrunnen intending to park at the big public car park in the middle of the village until I noticed how expensive it was. Sure enough, a couple of minutes down the road at the back of town was a smaller, less conspicuous place for less than half the price; it's often like that. The track started nearby and began by ascending forested cliffs to car-free Wengen on its sun terrace five hundred metres higher. As is somewhat typical of bigger resorts, I got briefly lost before finding the best way out of the village towards the higher ground to the south. Soon the track led past the Tschuggen's rather knobbly western slopes and then rounded a corner to face one of the most impressive panoramas in the whole of the Alps, that of the Eiger, Mönch and Jungfrau summits, at this point simply too big to fit into one photograph without special lenses. Just beyond, at Wengernalp station on the mountain railway, the Eiger loomed coldly, implausibly above the autumn grass slopes around Kleine Scheidegg, still half an hour away.

From Kleine Scheidegg a broad path suitable for all comers followed the contours on its way to the Männlichen lifts to the north, and a short distance down this path the Tschuggen summit, long hidden, finally came into view. The ridge to the right had a winter lift terminating halfway up it, and would offer the easiest ground for walking. Sure enough, it was no problem to leave the path near the lift cables and head up a mixture of grass and small scree. There was a brief confusion of rocks and hollows behind the terminus of the lift before the grass resumed, and there was nothing worse than a bit of steep, shaly ground before the grass once again predominated to the summit.

And what a summit! The Tschuggen is the best of all viewpoints for the big Oberland peaks, but it enjoys unobstructed views in every other direction too. For once, the early snow was a blessing, rendering the contrast between the Eiger and the Mönch and the busy autumnal slopes around Kleine Scheidegg even more striking than usual. To the east, Grindelwald and the Wetterhorn looked mellower in the afternoon sunshine, while far below on the other side, a tiny train was beginning the journey up the cog railway from Wengen towards the mountains.

After a hour or so surrounded by all this splendour, I set off down by the same way I had come. There was time to stop just outside the tourist hullabaloo of Kleine Scheidegg for a coffee at the Hotel Grindelwaldblick and one more look at that amazing backdrop before starting the long descent back to Lauterbrunnen.

The Grand Chavalard is a mountain in the Muverans Group at the extreme western end of the Bernese Alps. It lies in the canton of Valais and is, along with the Haut de Cry, one of a number of peaks which expose great slanted, rocky faces to the Rhône Valley, some two and a half kilometres below.

Though the weather was not particularly warm, three days of early

autumn sunshine had followed the last walk, and it was time to get out again.

The sunshine would not have been enough to remove all the fresh snow, but I

could always get more height by going to Switzerland's sun trap, the Rhône Valley,

where the south-facing slopes especially would be less likely to have snow.

Also, the Walking Friend wanted to come along, and it would be easy to pick him up on

the way.

Though the weather was not particularly warm, three days of early

autumn sunshine had followed the last walk, and it was time to get out again.

The sunshine would not have been enough to remove all the fresh snow, but I

could always get more height by going to Switzerland's sun trap, the Rhône Valley,

where the south-facing slopes especially would be less likely to have snow.

Also, the Walking Friend wanted to come along, and it would be easy to pick him up on

the way.

It only remained to pick a peak. In all the scores, if not hundreds, of times I had sped along the floor of the Rhône Valley by car or by train, I had never failed to notice two great peaks rising above the valley east of Martigny, the Grand Chavalard and the Haut de Cry. Their vast, roughly pyramidal faces towered nearly two and a half kilometres above the valley floor, promising wonderful views from their upper slopes. The Grand Chavalard had more direct access; it would be the one.

The pickup in Montreux accomplished, we continued down the Autobahn to Martigny and turned off to the riverside town of Fully, where we managed to find the road uphill. The nerve-wrackingly narrow road wound its way in many hairpins past the hamlets of Eulo and Chibo to a generous car park at the end of the road at a place called Erié, some fourteen hundred metres above the valley floor. I wouldn't normally have cut so much off an ascent, but there was the WF to take into account, and the two-and-a-half-hour journey from Burgdorf meant that there wasn't enough daylight to do the whole peak anyway.

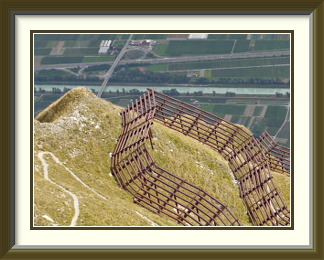

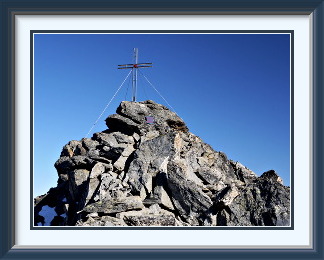

Out of the car at last, we headed along an easy path which climbed gently across the two thousand metre contour in the morning sunshine. Having rounded an impressive spur of the Grand Chavalard, we left the easy path for a smaller mountain track heading directly for the peak. This led soon to a steep gully, above which we were confronted with a novelty... a series of avalanche barriers protecting the villages far below. Sometimes the track skirted these, and sometimes it led directly through the barriers via rectangular slots, some of which are visible in the picture (e.g., towards of the right end of the fourth barrier from the bottom). With these left behind at last, the bare, triangular summit came into view, and the last part of the route consisted of an oddly uniform slope of shattered rock below the summit cross and (unfortunately) telecommunications tower.

The summit is a peerless viewpoint; being well separated from other peaks of similar height, it offers untrammelled views in every direction. To the west, the whole Mont Blanc Range is visible. Looking the other way, the heavily developed Rhône Valley stretches into the distance towards the high peaks of the Bernese Oberland. This summit is also one of the best placed to see the serrated tops of the Dents du Midi, but it is the view beneath which really sets this mountain apart. You look dizzily down the summit ridge to the village of Mazembroz, the heavily-controlled Rhône and the A9 Autobahn almost two and a half kilometres below.

After an hour or so drinking all this in, we set off down the way we had come, past those amusing avalanche barriers once more, to our car and the valley far beneath.

The First above Kandersteg is a peak on the ridge separating the Kander and the Engstligen (Adelboden) Valleys, from either of which it can be reached. Of no great distinction itself, it nevertheless offers good views of the Oeschinen Lake and the Doldenhorn and Blümlisalp summits.

Three more days of cool and fickle weather had passed since the walk up the Grand

Chavalard; things wouldn't have changed much on the heights, but I needed to get

out. Once again it would be best not to go too high. I remembered a summit I had seen

from the

Bonderspitz lying further north

along the chain of tops to the west of Kandersteg, and thinking at the time that I wasn't sure

I had ever ascended it.

Weather reports indicated a Föhn storm in the Bernese Oberland; southerly or

southwesterly gales would be barrelling over the tops and down into the valleys. It

would be wise to stay off tricky ground, and this peak,

The First,

was straightforward and easy of access.

Three more days of cool and fickle weather had passed since the walk up the Grand

Chavalard; things wouldn't have changed much on the heights, but I needed to get

out. Once again it would be best not to go too high. I remembered a summit I had seen

from the

Bonderspitz lying further north

along the chain of tops to the west of Kandersteg, and thinking at the time that I wasn't sure

I had ever ascended it.

Weather reports indicated a Föhn storm in the Bernese Oberland; southerly or

southwesterly gales would be barrelling over the tops and down into the valleys. It

would be wise to stay off tricky ground, and this peak,

The First,

was straightforward and easy of access.

There was indeed a gale blowing in Kandersteg, and with spitting rain there were not many tourists around. It was easy to find a parking spot at the back of the village, close to where the walk starts. A nearby signpost showed that there was lots to do for the visitor to Kandersteg! A weak sun shone fitfully as I set off, but lower down the valley there was stormy murk. The first part of the walk was a slog up steep forest, arriving at last at the end of a motorable road at a place called "Ryharts", probably the name of the farmer who owned the chalet there. As I walked the roughly level road, the storm clouds receded and there were pleasant views of Kandersteg six hundred metres below. After a while, the road turned a corner and for the first time I could see the First's summit. Soon I turned off the road, and the rest of the way was a slog up grass and bits of scree. Near the top, the track ran along the summit ridge, and with the wind as strong as ever, I found myself walking in the grass a few feet below the track to avoid being blown over the edge and down the steeper western side of the mountain.

From the summit I could see that the break in the clouds had grown much wider; the view stretched along the ridge to the distant Niesen and the plains. Despite the easy track, there was nobody around; this wasn't a day for the faint-hearted. I held my lunch tight to stop it flying away as I looked around at the scenery. Kandersteg and the Oeschinensee looked deceptively calm at this distance, but the storm clouds still raced over the Doldenhorn.

Heading back down the unfamiliar path (for it was unfamiliar... I had indeed never before done the First), I could see cigar-shaped cumulus clouds typical of Föhn storms. This one didn't slacken off either... back in Kandersteg, I was briefly soaked when a particularly fierce gust lifted spray off the Kander stream as it flowed beside the road.

The Almagellerhorn is a mountain in the Saas Valley above the village of Saas-Almagell from which it can be reached. A straightforward track leads via the upper station of a skilift at Heitbodme to a terrace called the Panoramaplatz. A short via ferrata is needed to get from there onto the upper part of the mountain, which remains steep the rest of the way to the summit. There are excellent views of the Mischabel Group and other 4000ers, especially the nearby 4017-metre Weissmies.

The four days since the last walk had been nothing special; initial rain had given way to

dry conditions ranging from cool to slightly cold. It was unlikely that the snow on the

heights of the Bernese Oberland would have retreated usefully. To go higher, I would have

to visit the Rhône Valley area again if I wanted to find something challenging.

The Saas Valley on its south side was

somewhere I had not been for many years, despite its large number of walking tracks, so

once again I was up early, onto the train through the Lötschberg Tunnel and into the

Valais as fast as my tyres could take me. The Almagellerhorn promised a good, stiff walk.

The four days since the last walk had been nothing special; initial rain had given way to

dry conditions ranging from cool to slightly cold. It was unlikely that the snow on the

heights of the Bernese Oberland would have retreated usefully. To go higher, I would have

to visit the Rhône Valley area again if I wanted to find something challenging.

The Saas Valley on its south side was

somewhere I had not been for many years, despite its large number of walking tracks, so

once again I was up early, onto the train through the Lötschberg Tunnel and into the

Valais as fast as my tyres could take me. The Almagellerhorn promised a good, stiff walk.

Parked at the entrance to Saas Almagell, I set off through the cold morning air along what looked like a perfectly reasonable path, but soon found myself descending through the forest to the upper end of the village, where there was more parking by the Furggstalden chairlift. Twenty minutes wasted through not aggressively seeking the best parking place! From the chairlift, a path led properly upwards through the trees past the hamlet of Furggstalden and across fairly uninspiring ground, where it seemed at times to be using easy winter ski runs, a slow way to to gain height. There were also very few markings, so I took a mental picture of every fork I passed. Finally the scenery began to improve, with a view up the bleak Furgg Valley towards the Antronapass on the Italian border. Rising a little more steeply, the track passed the terminus of the Heitbodme ski lift, a lovely place to stop for a coffee, had its summer season not already ended. Not far beyond this, the track turned off the main path towards Italy and arrived at a viewpoint called the Panoramaplatz, looking down on Saas Almagell and Saas Fee.

So far, so T2, but that now ended. The southwest ridge of the mountain began with an assisted stretch, including a cable which wasn't always securely fixed, and the remaining six hundred or so metres to the top consisted of big rubble at a fairly steep angle. The route was well marked with white-blue-white paint, but care was still needed not to miss one of its many twists and turns through the somewhat featureless jumble. At last, the white pole marking the best access to the summit ridge appeared, and minutes later I was standing before the summit, an exceptional viewpoint, albeit one with less than optimal seating options.

And there really was a lot to see. Looking southeast along the jagged ridge, I could now see over the Antronapass into Italy, which must have been having a rather depressing day to judge from the cloud cover. To the west, some of Switzerland's highest peaks uttered rivers of ice towards the Saas Valley. Right across the Almageller Valley, the Weissmies looked surprisingly harmless for a four-thousander, with the tiny Almagell Hut blending into its mellow-coloured scree slopes to the point of effective invisibility. Drenched in the afternoon sun, the slopes traversed by the track to the hut had a texture reminiscent of some of the Australian landscapes I often overfly on the way to and from Europe.

The descent through all that rubble was long and careful, with a delay when the markings gave out at one big turn, and only caution and a search saved me from going far astray. By the time I was back on the easy path and passing the Heitbodme ski lift the sun had set, and the last hour of the descent was done wearing my headlamp in total darkness. That was where those mental pictures made things a whole lot easier!

The Kaiseregg is a mountain in the Fribourg Alps lying to the east of the small ski resort of Schwarzsee. The summit offers fine views of the main Alpine chain to the east and west, with only the views to the south being obstructed by the slightly higher Schafberg.

Three more days had passed since the last walk with no sign of the Indian summer

one might have hoped for in late September. There had been some sun, but snow had

fallen as low as 1300 metres in the Bernese Oberland on the second day. Now a day

of calm and sunny weather was promised, so there was no use in waiting for something

better. Also, the Congenial Swiss Lady was once again free to join in,

and there were plenty of summits in the Prealps where a

little fresh snow wouldn't cause us problems. We settled on the Kaiseregg in

Canton Fribourg. It looked down on a pleasant lake called the Schwarzsee, and I

hadn't been there in ten years.

Three more days had passed since the last walk with no sign of the Indian summer

one might have hoped for in late September. There had been some sun, but snow had

fallen as low as 1300 metres in the Bernese Oberland on the second day. Now a day

of calm and sunny weather was promised, so there was no use in waiting for something

better. Also, the Congenial Swiss Lady was once again free to join in,

and there were plenty of summits in the Prealps where a

little fresh snow wouldn't cause us problems. We settled on the Kaiseregg in

Canton Fribourg. It looked down on a pleasant lake called the Schwarzsee, and I

hadn't been there in ten years.

After picking her up it was no more than an hour to the Schwarzsee, and soon we were leaving the modest lakeside resort behind. Much of the early ascent was through farmland, with the early snows much in evidence ahead. Some development is taking place, though, and a modern-looking ski lift station wasn't there ten years ago. Along this part of the path, the morning view of the horseshoe of peaks encircling the Breccaschlund was marred only by some unfortunate electricity pylons. Soon we were crunching our way up the northern side of the mountain to the little Kaiseregg Pass, where the Schafberg burst into view, its sunless northern wall looking more severe than usual.

Now we were on the sunny side of the mountain, and the rest of the way was free of snow. At the summit, a small crowd was coming and going, some even having brought wine for their lunch. This was a day when the experience was if anything enhanced by the presence of a little snow. There was the more or less obligatory panorama of the high Oberland, but the view on the other direction was just as interesting. Beyond the jumble of nearby tops the little Dent de Broc was silhouetted against a cloud and the view stretched all the way to the Diablerets on the horizon. Below we could see the Schwarzsee and a good part of our path back to the car park.

The Mont de l'Etoile is a mountain in the Pennine Alps lying between Les Haudères in the Val d'Hérens to its east and the Grande Dixence dam to its west. It overlooks the Vouasson Glacier on its northwest side, while its southwestern slopes are ice-free.

During the last few days of September the weather was stable and cool, and there

had been no more precipitation since the last walk. Neither had there been any warm winds

to melt the snow that had fallen earlier in the month though, so if I wanted to end the

2015 season on a high note, I would need to choose somewhere in the Valaisian Alps

once more. This time, I would pick a valley in the French-speaking part; the choice

fell on the Val d'Arolla, where I had never been, and the Mont de l'Etoile on its

western side.

During the last few days of September the weather was stable and cool, and there

had been no more precipitation since the last walk. Neither had there been any warm winds

to melt the snow that had fallen earlier in the month though, so if I wanted to end the

2015 season on a high note, I would need to choose somewhere in the Valaisian Alps

once more. This time, I would pick a valley in the French-speaking part; the choice

fell on the Val d'Arolla, where I had never been, and the Mont de l'Etoile on its

western side.

Getting out of the car in the hamlet of La Gouille near the end of the valley, there was a reminder that the season was nearing its end; the temperature at eight thirty was just 2°C. Conditions were still and cloudy on the ascent past the Lac Bleu, a local beauty spot of fairly modest beauty, and up through a high alpine meadow with an abandoned hut. The last vegetation was fading away below the Cabane des Aiguilles Rouges; it wasn't worth the short detour to visit it, as the bare flagpole meant that it was closed for the winter. No need for signposts here, with an enormous boulder marking the path to the hut. Around a corner, the summit came into view beyond a stony wilderness and the moraine of a long-gone glacier. The path ran along the top of this moraine until another big boulder announced the divergence of my track from the blue markers of the route up the Pointe de Vouasson. For some reason, the track up the Mont de l'Etoile has white-green-white markings, not a standard colour combination in the Swiss Alps. It became steeper just below the summit and crossed some surprisingly dark scree.

The usual relief at approaching the small summit cairn evaporated when I stood beside it and saw that I was only on a forepeak. A higher summit and a much bigger cairn lay ahead over trickier ground. Nevertheless, it was only a matter of a few minutes to reach it, and then, aaarghh!, another summit with a big cairn loomed further away. However, after careful consideration, I decided I was already at the highest point1 and decided not to continue. The cairn fairy must have had an off day here, for the monster cairn was listing seriously; it wouldn't surprise me if it left for the valley fairly soon. Rising cloud hid the view in some directions, but still left plenty to see. Beyond the small cairn on the first top, the Aiguilles Rouges reached for the sky, and at the back of the Arolla Valley, sun and cloud played around Mont Collon and its glaciers.

I enjoyed a leisurely lunch at the summit before heading back down over the arid scree of the peak and the long, stony moraine to the the point where the stones gave way gently to the first growth and then past the Lac Bleu to the world of living things and the road home.